Why You Shouldn't Try To Time The Market

Image by Sergei Tokmakov, Esq. https://Terms.Law from Pixabay

As I write this on April 11th, 2025, market volatility as measured by the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) is as high as it's been since the 2020 pandemic. And if we take the pandemic out as an outlier, it's the highest it's been since 2011. In the last couple of weeks, we've seen the best market days and the worst market days in years, and the market has become very sensitive to news and seems to be moving faster than ever.

This is when the old adage to "stick to the plan" can, admittedly, become a test of human will. We do everything we are supposed to do ahead of time, create a financial plan that can withstand market ups and downs, agree on the right risk level for your portfolio, and have a plan for rebalancing. But when it comes down to brass tacks, it can be hard to resist the urge to "time the market." But there are several reasons I'll outline below why deviating from your intended investment plan and trying to outsmart the stock market is done at your own peril.

What is "Timing the market?"

Simply put, timing the market is attempting to buy into or sell out of the market at the just right time. Stocks cycle up and down day to day, week to week. Stocks have up days more often than down days, but there is no escaping the bumpy ride it can sometimes be. Someone who thinks they can time the market believes they can sell right before the market goes down (or declines more) and can buy right at the bottom before stocks head up. The stock market can behave very irrationally, though, and believing you can forecast the market movements is like predicting which pictures will appear on the slot machine's next pull.

There always feels like a reason to jump out of the market.

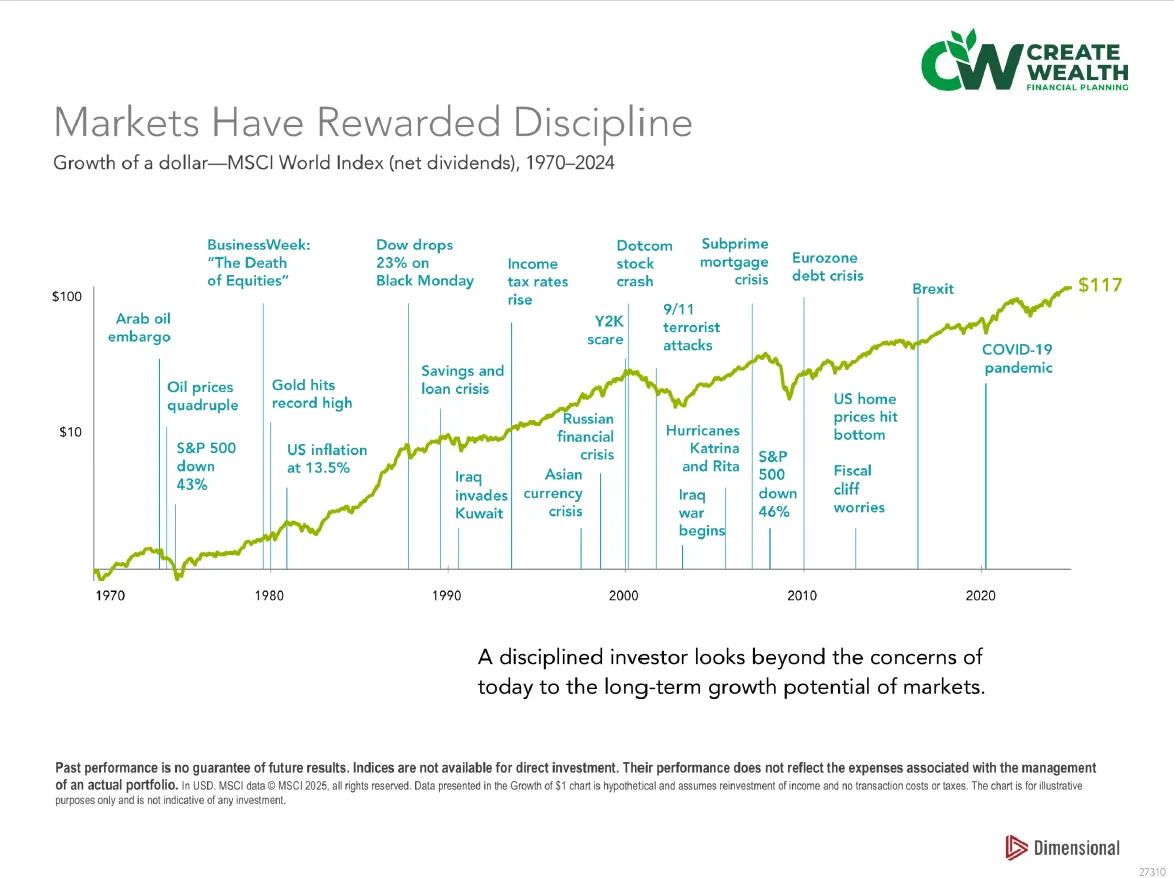

"This time it's different" is a phrase that often comes before deciding to sell everything and exit the market. While it's true the reasons for volatility are different this time (tariffs), just like they were the last time (pandemic), the time before that (housing bubble), and the time before that (tech bubble), the outcomes tend to follow similar patterns. As the chart above shows, every steep market downturn was followed up by an eventual recovery, often a fairly quick one, with many bear markets fully recovering within a year. There always feels like a reason to jump out, but the market marches on.

Missing just a few big days hurts.

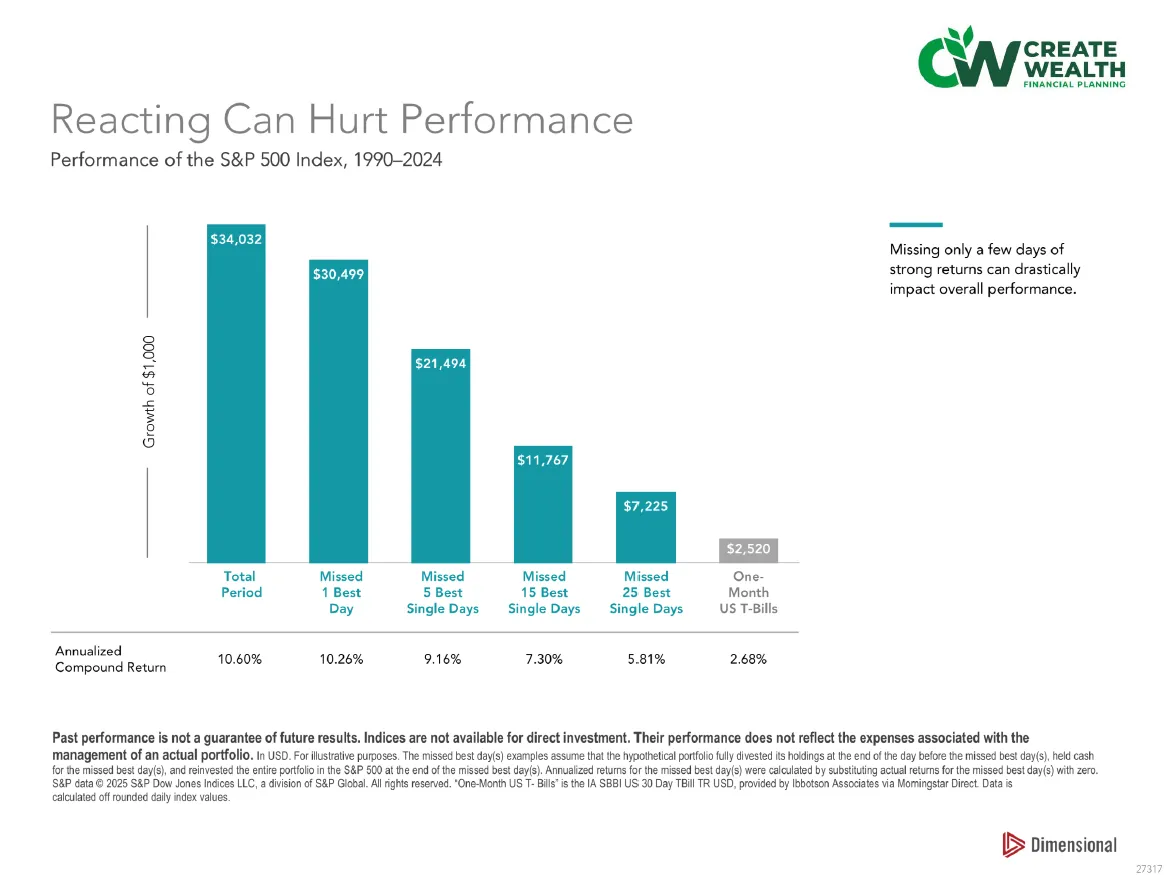

"Time in the markets beats timing the markets." You have to know when to get out, and you have to know when to get back in. As mentioned, the downturns can be quick, and the recoveries can be even faster. The market can move in fits and starts, and what shows up at the end of the year as an annual return is often made up of a few big days during the year. The above chart highlights the difference between an investor who put $1,000 into the S&P 500 in 1994 and stayed in versus an investor who missed just a few of the highest returning days during that same period. The investor who stayed the course did so during the Dot.com Bubble, the Great Recession, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and everything in between until 2024. The investors who got cold feet, even just for a day, potentially got left with much less in their investment accounts. Do YOU know when the best 25 days of the next 35 years will be? If not, it is better just to stay in the market.

Timing the market means you have to be right twice.

Markets are forward-looking. The stock market adjusts to lousy news very quickly, and once it's done that, it starts looking beyond the bad news for better days ahead. This means the stock market recovery often begins while the worst news is still to come. It may not feel terrific to jump back into the market in the depths of a recession, but by then, the market is usually looking past the recession and ready to move up again. Two examples from recent history make that very clear.

- The Great Recession: After beginning its decline in November 2007, the S&P 500 bottomed out in March 2009. The National Bureau of Economic Research didn't declare the end of the recession until June 2009, and the unemployment rate did not peak until October 2009. The S&P 500 was up a whopping 55% from the bottom in March 2009 through Halloween 2009. Would you have bought in while GDP was still declining and unemployment was still rising?

- The COVID-19 pandemic: The step drawdown in the early days of the pandemic sent the S&P 500 down 33% in a month from February 20th to March 23rd. If you had gotten out at the beginning of the decline, would you have been ready to buy in with the worst of the pandemic still ahead of us? It was a terrifying time not just as an investor but as a human as we dealt with quarantines, school and business closures, and most importantly, the loss of loved ones. But the market had already begun to see through to the other side well before most of the rest of us could imagine it, recovering all the losses by August and ending up 18% for the year.

Switching has costs in taxable accounts.

Timing the market isn't entirely a free lunch. While there was a time when commissions would eat away at a portfolio, commission-free trading and no transaction fee mutual funds have made that largely avoidable.

Where switching still has highly relevant costs are in taxable brokerage accounts. Recessions and market corrections often come after significant gains in the market, making things a little "top-heavy." With big capital gains comes a potential tax bill if you sell everything and move to cash. To make matters worse, if you do get lucky and buy back in low, prepare to build up more capital gains again on investments you already owned before. And if you wait too long to reinvest and wind up buying back in closer to where you left the market, well, you just racked up a capital gains tax bill you didn't have to, and you're worse off than when you started.

Now, I recognize you only pay taxes on the money you make, and if you're lucky enough to get out at the top and get back in at the bottom, the tax bill will be less than the benefit of the trade. But it is still a cost you have to recognize; it reduces the overall value of the trade and raises the bar on being right even higher because not only do you have to get out and get in at the right time, you have to stay ahead of your tax bill as well.

So what CAN you do?

I am suggesting you avoid marketing timing, but I am not suggesting you sit on your hands, either. You can make moves in a volatile market, and if you aren't comfortable reacting to your portfolio yourself, you can partner with a professional to offer support.

- Rebalance - with big market drops, your portfolio mix can get out of whack. Let's say you set a goal to have a portfolio with 80% stocks. A market decline has left your portfolio at only 75% stocks. By rebalancing, you return your portfolio to the target of 80%. Instead of trying to time the next move, you are simply reacting to what has occurred to ensure your portfolio is in position for an eventual recovery. It also provides a natural way to make some buys when the market is down.

- Assess your portfolio goals—We always discuss with investors their risk tolerance, goals, and purpose of their money. In times like this, risk tolerance gets put to the test. It's a good time to ask yourself if your portfolio is still aligned with your long-term goals and if you have an investment mix that you can live comfortably with.

- Tax-loss harvesting - Sharp declines like this can create losses in your accounts. Bad timing on investments happens, and with markets moving up and down unpredictably, there will be times when you put some money to work right before a downturn. I can guarantee it. Tax-loss harvesting (read more in the linked article) allows you to take those losses for tax purposes, buy a similar investment (but not too similar), and create a tax write-off without getting out of the market. Tax losses can offset gains you take in other areas of the portfolio or offset up to $3,000/year in regular income until the loss is used up. When the stock market hands you a lemon, it's a way to make lemonade.

So when your investment advisor says to "stay the course" and "remain calm," it can be tough to hear sometimes. "Easy for you to say," you might think, "It's my money after all!" In our defense, we are simply using history as a guide, that staying invested really does pay off, that timing the market is much more difficult than some make it out to be (dare I say impossible without a good bit of luck), and that if you think watching the market decline with your money in it feels terrible, watching the market go back up while you're sitting on the sidelines might feel worse.